I've been sitting on these notes since seeing Boyhood back in August. The comparisons I makes here have some significant gaps, but I didn't want to scrap the idea. I also didn't want spend more time developing it, so here it is.

Perhaps it's because I watched both Boyhood and American Dreams: Lost and Found in the same day, or because Gabe Klinger's recent documentary Double Play puts Linklater and Benning in the same sentence, but I can't separate the two films in my thoughts. American Dreams: Lost and Found provides the structural basis for Boyhood.

The experience of watching American Dreams almost demands that one parse out the distinct elements that comprise the film. While any film is more than the sum of its parts, American Dreams encourages this kind of contemplation because of the clear visibility of each component. It has three main elements:

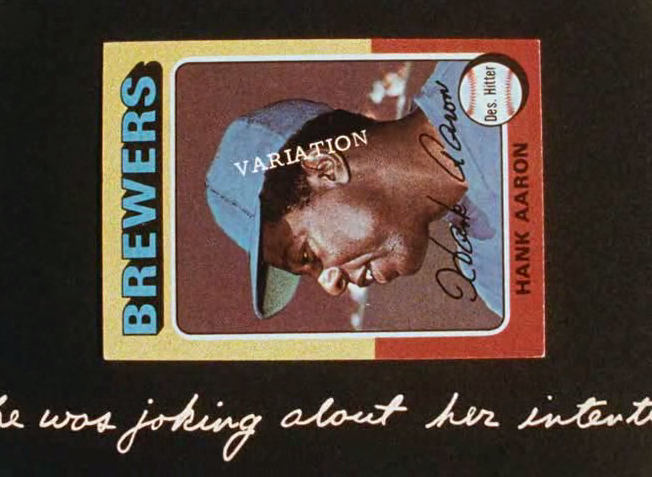

1. The visual: photographed ephemera (primarily Hank Aaron baseball cards).

2. The sonic: recordings that bear the texture of historically and geographically specific pieces (alternatively political recordings and radio singles).

3. The textual: scrolling handwritten text of the diaries of Arthur Bremer, the man who shot Gov. George Wallace.

There are also two other elements that are crucial to the film's totality:

4. The descriptive text that appears to contextualize the audio.

5. The mat-black background that the images and text appear over.

With the exception of the descriptive texts that come and go, these elements are constantly in play in equal measure for the duration of the film, although not every element can be consumed at the same time. For a moment you may be more engrossed in the music or the content of the political speeches and for others you might be hanging on every word from Bremer's diary (occasionally an overlapping white frame makes the scroll difficult to read, but this has the effect of making the words even more enticing).

Each element has its own set of rhythms and contours, like a jazz piece. The audio recordings are of widely experienced historical events, broadcast nationwide through the latest media technology, mixed with a carefully curated historiography of radio singles, from the Del Vikings to Donna Summer. The photographed ephemera are almost exclusively baseball cards of Hank Aaron, producing a photographic archive of one specific historical and cultural figure. And the scroll is the idiosyncratic thoughts of an individual who lived through the historical moments collected here, but who only became widely known (that is, an historical figure like Elvis or Richard Nixon) because of his assassination attempt of a widely-known public official. Thus, we experience the private, anonymous thoughts of a figure before they became a figure, with the film climaxing in the moment when Bremer transcends obscurity and is thrust into the public/historical stage, retroactively transforming his private diaries into the ephemera of celebrity.

The elements intersect in interesting ways. The scroll writes about Richard Nixon, whose press conferences are among the film's audio selections which also include an interview with Hank Aaron and the film's concluding audio of Aaron hitting his 500th home run. There is also the prominent convergence of the scroll detailing the plans to assassinate Wallace, which culminates in the news audio recording of the shooting.

Boyhood shares much of this basic elemental structure. The film features three dominant elements:

1. The fictional narrative structure which allows for the documentation of the actual aging of the performers (perhaps this is two elements).

2. The photographed documentation of the visual textures of the period, primarily video games like Halo and Pokemon, but also widely seen televised news events.

3. The soundtrack that functions as a historiography of radio singles (Coldplay, Soulja Boy) and political speeches (Obama, Bush).

Clearly, there is no 1:1 comparison, and my arguments will most likely fall apart on closer examination, but I think it worth while to ponder the similarities. The fictional narrative of Boyhood, while dissimilar to Bremer's diaries, does present the private documentation of personal transformation over the course of the film's production. Naturally, this production was made with the intent of being released as a finished product, but in a not too-dissimilar fashion the subjects of the film are transformed from anonymous performers (sans the stars) into public figures largely because of the documentation of their ephemeral existence. Their childhoods are public now, but they are not child stars, since they will never perform as children again. How can they?

More appropriate for comparison is the meticulous documentation of the mainstream cultural landscape of a decade. Where Benning reconstructed the 1950s to the 1970s, Linklater constructs the early 2000s to the mid 2010s. This landscape is preoccupied with visual textures (largely those associated with masculine youth) and a ubiquitous audio palette.

Interesting in both is the absence of counter culture, but both transform homogenous popular culture into something radical through the framing and presentation.

No comments:

Post a Comment