"As a result of saying it can show anything, cinema has abandoned the power over the imagination. And, like cinema, this century is perhaps starting to pay a high price for this betrayal of the imagination - or, more precisely, those who still have an imagination, albeit a poor one, are being made to pay that price."

***

When I heard of Chris Marker's death I wandered back into that magnificent mess of his, where The Legend of Bruce Lee occupies cherished shelf space:

From Agnès Varda's Agnès de ci de là Varda, Episode 1, 2011.

I'm curious to note what Marker's thoughts were on the Obama presidency. Did he, like most cautiously supportive radical leftists, recoil in horror? Here we are only given pre-election imagery.

***

Then I watched Vertigo.

from Marker's A Free Replay (notes on Vertigo):

which reminds me...

"Obviously, this text is addressed to those who know Vertigo by heart. But do those who don't deserve anything at all?" [search this passage and you'll fine the entire pdf]

"In this case, the entire second part would be nothing but a fantasy, revealing at last the double of the double. We were tricked into believing that the first part was the truth, then told it was a lie born of a perverse mind, that the second part contained the truth. But what if the first part really were the truth and the second the product of a sick mind"

which reminds me...

"What Scottie first experiences in Vertigo is the loss of Madeleine, his fatal love; when he recreates Madeleine in Judy and then discovers that the Madeleine he knew actually was Judy pretending to be Madeleine, what he discovers is not simply that Judy was faking (he knew that she was not the true Madeleine, since he had recreated a copy of Madeleine out of her), but that, because she was not faking - she is Madeleine, Madeleine herself was already a fake - the objet a disintegrates, the very loss is lost, and we see a 'negation of negation'. His discovery changes the past, deprives the lost object of the objet a."

-Slavoj Žižek, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Lacan But Were Afraid to Ask Hitchcock

Marker deserves the last word here:

"Scottie experiences the greatest joy a man can imagine, a second life, in exchange for the greatest tragedy, a second death. What do video games, which tell us more about our unconscious than the works of Lacan, offer us? Neither money nor glory, but a new game. The possibility of playing again. 'A second chance.' A free replay."

***

***

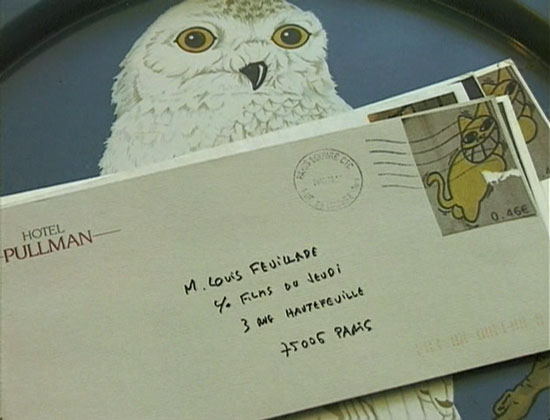

6 August. Encounters. Chris Marker is in town. He goes back to

where he's been and films "randomly", rather happy to have emerged from

the adventure of A Grin Without a Cat. His friend Terayama shoots in HK.

The festival staff organises a lunch. Marker tells me that HK (which he

doesn't like) has changed a lot. He comes from Okinawa and is on his

way to China where he hasn't been since Sundays in Beijing. During the

meal (on a very hot day), we talk about several things: Bruce Lee's

mysterious death, the rumour that the Red Army guards may have filmed

things during the cultural revolution. What happened to these films?

Will we see them one day? What do they do with films over there? Do they

archive them? Someone shows me the press clip of a Chinese newspaper

talking about the fire at the warehouse of the Cinémathèque française.

And also, why preserve / curate? Cinema will perhaps have been the

collective dream of the 20th century? Marker is going to take pictures

in Cat Street. We leave each other. - Serge Daney, Cahiers du Cinéma 1981 (X)

***

***

"With all due reverence, I—to be honest—sometimes wonder whether there is not something coy and self-indulgent in the private mythology Marker has been spinning over the years: his grinning cats, his owls, Guillaume-en-Egypte, his female assistants . . . And the somewhat loose hermetic nature of his pronouncements frustrate the essayist in me, who would prefer that he grapple with what he seems to mean and wrest as much clear understanding as can be had. It strikes me as peculiar that our greatest essay-filmmaker should traffic so willingly in the enigmatic, the borderline-sentimental, and the faux-naïve."

"What also disturbs me is that those who have personal access to the Master, through e-mail correspondence and personal visits, have set up such a fond protection wall around him against critical judgment, accepting everything that emanates from him as a kind of indivisible pre-posthumous miracle, that it inhibits the making of distinctions about his stronger and weaker expressions. On the other hand, maybe I should just calm down and accept whatever is given me from Marker’s reshuffling of archives in the proper spirit of gratitude." (X)

These selections from Phillip Lopate were plucked for scrutiny by Adrian Martin in Chris Marker: Notes in the Margins of His Time for Cineaste Vol. XXXIII No. 4 (Fall 2008).

from that same issue comes this curio, the lone footnote in Marker's piece The Last Bolshevik: Reminiscences of Alexander Ivanovich:

"Just before he died in 1988, Jay Leyda was working on a monumental Medvedkin anthology, including his diary of the train [the Kinopoezd], scripts from the movies, and lots of critical pieces. Then he passed away, and I never heard anything further about the project, as if it never existed. A true mystery. If anyone has any information about this, or knows the whereabouts of Leyda's Medvedkin materials, please contact me c/o Cineaste."

***

***

"Godard nailed it once and for all: at the cinema, you raise your eyes to the screen; in front of the television, you lower them. Then there is the role of the shutter. Out of the two hours you spend in a movie theater, you spend one in the dark. It's this nocturnal portion that stays with us, that "fixes" our memory of a film (the way you fix color on a canvas) in a different way than the same film seen on television or on a monitor. But having said that, let's be honest. I've just watched the ballet from An American in Paris on the screen of my iBook, and I very nearly rediscovered the exhilaration that we felt in London, in 1952, when I was there with Alain Resnais and Ghislain Cloquet, during the filming of Statues Also Die, when we would start every day by seeing the 10:00 a.m. show of An American in Paris at a theater in Leicester Square. An exhilaration that I feared I had lost forever when watching the film on cassette."

"I have a completely schizophrenic relationship with television. When I assume I'm the only one in the world, I adore it, particularly since there's been cable. It's curious how cable offers an entire catalog of antidotes to the poisons of standard TV [...] Now there are moments when I remember I am not alone in the world, and that's when I fall apart. The exponential growth of stupidity and vulgarity is something that everyone has noticed, but it's not just a vague sense of disgust--it's a concrete, quantifiable fact (you can measure it by the volume of the cheers that greet the talk-show hosts, which have grown by an alarming number of decibels in the last five years) that comes close to a crime against humanity [...] I must say the worst: I am allergic to commercials. In the early sixties, that allergy was rather well considered. Today it's unavowable." (X)

from an interview by Samuel Douhaire and Annick Rivoire for Libération, translated by Marker for publication in the Criterion release of La jetée + Sans Soleil.

***"To be able to play the games of culture with the playful seriousness which Plato demanded, a seriousness without the 'spirit of seriousness', one has to belong to the ranks of those who have been able, not necessarily to make their whole existence a sort of children's game, as artists do, but at least to maintain for a long time, sometimes a whole lifetime, a child's relation to the world. (All children start life as baby bourgeois, in a relation of magical power over others and, through them, over the world, but they grow out of it sooner or later.) This is clearly seen when, by an accident of social genetics, into the well-policed world of intellectual games there comes one of those people (one thinks of Rousseau or Chernyshevsky) who bring inappropriate stakes and interests into the games of culture; who get so involved in the game that they abandon the margin of neutralizing distance that the illusio (belief in the game) demands; who treat intellectual struggles, the object of so many pathetic manifestos, as a simple question of right and wrong, life and death. This is why the logic of the game has already assigned them roles--eccentric or boor--which they will play despite themselves in the eyes of those who know how to stay within the bounds of the intellectual illusion and who cannot see them any other way."

-Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste

***

a personal note

My first encounter with Chris Marker was entirely by chance - in fact I hadn't even known I had encountered him. It was my first viewing of Alain Resnais' Night and Fog, screened, not for a film class, but for one on the Holocaust, where I first witnessed the power of the visual essay. Marker's contributions go uncredited, a secret collaborator that is absent even from the liner notes of the Criterion DVD.

It seems strangely fitting that my last encounter with him during his own lifetime was a return to the concentration camps*, where in interview he concludes by discussing two artists destined for greatness who died in the camps: François Vernet and Viktor Ullmann. Ullmann is as good as any place to stop.

It seems strangely fitting that my last encounter with him during his own lifetime was a return to the concentration camps*, where in interview he concludes by discussing two artists destined for greatness who died in the camps: François Vernet and Viktor Ullmann. Ullmann is as good as any place to stop.

*Oddly

enough, on the date of Marker's birth, July 20th, 1921, Adolf Hitler

was publicly introduced as party chairman of the National Socialist

German Worker's Party (according to some sources, others say it was the the 28th or 29th). This is perhaps the first time I've regretted putting my Shirer texts in storage.

No comments:

Post a Comment